Proposition 11.23

To construct a solid angle out of three plane angles two of which, taken together in any manner, are greater than the remaining one: thus the three angles must be less than four right angles.

To construct a solid angle out of three plane angles two of which, taken together in any manner, are greater than the remaining one: thus the three angles must be less than four right angles.

Let the angles ABC, DEF, GHK be the three given plane angles, and let two of these, taken together in any manner, be greater than the remaining one, while, further, the three are less than four right angles; thus it is required to construct a solid angle out of angles equal to the angles ABC, DEF, GHK.

Let AB, BC, DE, EF, GH, HK be cut off equal to one another, and let AC, DF, GK be joined; it is therefore possible to construct a triangle out of straight lines equal to AC, DF, GK. [XI. 22]

Let LMN be so constructed that AC is equal to LM, DF to MN, and further GK to NL, let the circle LMN be described about the triangle LMN, let its centre be taken, and let it be O; let LO, MO, NO be joined; I say that AB is greater than LO.

For, if not, AB is either equal to LO, or less.

First, let it be equal.

Then, since AB is equal to LO, while AB is equal to BC, and OL to OM, the two sides AB, BC are equal to the two sides LO, OM respectively; and, by hypothesis, the base AC is equal to the base LM; therefore the angle ABC is equal to the angle LOM. [I. 8]

For the same reason the angle DEF is also equal to the angle MON, and further the angle GHK to the angle NOL;

But the three angles LOM, MON, NOL are equal to four right angles; therefore the angles ABC, DEF, GHK are equal to four right angles.

But they are also, by hypothesis, less than four right angles: which is absurd.

Therefore AB is not equal to LO.

I say next that neither is AB less than LO.

For, if possible, let it be so, and let OP be made equal to AB, and OQ equal to BC, and let PQ be joined.

Then, since AB is equal to BC, OP is also equal to OQ, so that the remainder LP is equal to QM.

Therefore LM is parallel to PQ, [VI. 2] and LMO is equiangular with PQO; [I. 29] therefore, as OL is to LM, so is OP to PQ; [VI. 4] and alternately, as LO is to OP, so is LM to PQ. [V. 16]

But LO is greater than OP; therefore LM is also greater than PQ.

But LM was made equal to AC; therefore AC is also greater than PQ.

Since, then, the two sides AB, BC are equal to the two sides PO, OQ, and the base AC is greater than the base PQ, therefore the angle ABC is greater than the angle POQ. [I. 25]

Similarly we can prove that the angle DEF is also greater than the angle MON, and the angle GHK greater than the angle NOL.

Therefore the three angles ABC, DEF, GHK are greater than the three angles LOM, MON, NOL.

But, by hypothesis, the angles ABC, DEF, GHK are less than four right angles; therefore the angles LOM, MON, NOL are much less than four right angles.

But they are also equal to four right angles: which is absurd.

Therefore AB is not less than LO.

And it was proved that neither is it equal; therefore AB is greater than LO.

Let then OR be set up from the point O at right angles to the plane of the circle LMN, [XI. 12] and let the square on OR be equal to that area by which the square on AB is greater than the square on LO; [Lemma] let RL, RM, RN be joined.

Then, since RO is at right angles to the plane of the circle LMN, therefore RO is also at right angles to each of the straight lines LO, MO, NO.

And, since LO is equal to OM, while OR is common and at right angles, therefore the base RL is equal to the base RM. [I. 4]

For the same reason RN is also equal to each of the straight lines RL, RM; therefore the three straight lines RL, RM, RN are equal to one another.

Next, since by hypothesis the square on OR is equal to that area by which the square on AB is greater than the square on LO, therefore the square on AB is equal to the squares on LO, OR.

But the square on LR is equal to the squares on LO, OR, for the angle LOR is right; [I. 47] therefore the square on AB is equal to the square on RL; therefore AB is equal to RL.

But each of the straight lines BC, DE, EF, GH, HK is equal to AB, while each of the straight lines RM, RN is equal to RL; therefore each of the straight lines AB, BC, DE, EF, GH, HK is equal to each of the straight lines RL, RM, RN.

And, since the two sides LR, RM are equal to the two sides AB, BC, and the base LM is by hypothesis equal to the base AC, therefore the angle LRM is equal to the angle ABC. [I. 8]

For the same reason the angle MRN is also equal to the angle DEF, and the angle LRN to the angle GHK.

Therefore, out of the three plane angles LRM, MRN, LRN, which are equal to the three given angles ABC, DEF, GHK, the solid angle at R has been constructed, which is contained by the angles LRM, MRN, LRN. Q. E. F.

LEMMA.

But how it is possible to take the square on OR equal to that area by which the square on AB is greater than the square on LO, we can show as follows.

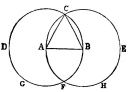

Let the straight lines AB, LO be set out, and let AB be the greater; let the semicircle ABC be described on AB, and into the semicircle ABC let AC be fitted equal to the straight line LO, not being greater than the diameter AB; [IV. 1] let CB be joined

Since then the angle ACB is an angle in the semicircle ACB, therefore the angle ACB is right. [III. 31]

Therefore the square on AB is equal to the squares on AC, CB. [I. 47]

Hence the square on AB is greater than the square on AC by the square on CB.

But AC is equal to LO.

Therefore the square on AB is greater than the square on LO by the square on CB.

If then we cut off OR equal to BC, the square on AB will be greater than the square on LO by the square on OR. Q. E. F.