Proposition 10.53

To find the sixth binomial straight line.

To find the sixth binomial straight line.

Let two numbers AC, CB be set out such that AB has not to either of them the ratio which a square number has to a square number; and let there also be another number D which is not square and which has not to either of the numbers BA, AC the ratio which a square number has to a square number.

Let any rational straight line E be set out, and let it be contrived that, as D is to AB, so is the square on E to the square on FG; [X. 6, Por.] therefore the square on E is commensurable with the square on FG. [X. 6]

And E is rational; therefore FG is also rational.

Now, since D has not to AB the ratio which a square number has to a square number,

Again, let it be contrived that, as BA is to AC, so is the square on FG to the square on GH. [X. 6, Por.]

Therefore the square on FG is commensurable with the square on HG. [X. 6]

Therefore the square on HG is rational; therefore HG is rational.

And, since BA has not to AC the ratio which a square number has to a square number, neither has the square on FG to the square on GH the ratio which a square number has to a square number; therefore FG is incommensurable in length with GH. [X. 9]

Therefore FG, GH are rational straight lines commensurable in square only; therefore FH is binomial. [X. 36]

It is next to be proved that it is also a sixth binomial straight line.

For since, as D is to AB, so is the square on E to the square on FG, and also, as BA is to AC, so is the square on FG to the square on GH, therefore,

But D has not to AC the ratio which a square number has to a square number; therefore neither has the square on E to the square on GH the ratio which a square number has to a square number; therefore E is incommensurable in length with GH. [X. 9]

But it was also proved incommensurable with FG; therefore each of the straight lines FG, GH is incommensurable in length with E.

And, since, as BA is to AC, so is the square on FG to the square on GH, therefore the square on FG is greater than the square on GH.

Let then the squares on GH, K be equal to the square on FG;

But AB has not to BC the ratio which a square number has to a square number; so that neither has the square on FG to the square on K the ratio which a square number has to a square number.

Therefore FG is incommensurable in length with K; [X. 9] therefore the square on FG is greater than the square on GH by the square on a straight line incommensurable with FG.

And FG, GH are rational straight lines commensurable in square only, and neither of them is commensurable in length with the rational straight line E set out.

Therefore FH is a sixth binomial straight line. Q. E. D.

LEMMA.

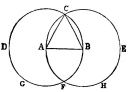

Let there be two squares AB, BC, and let them be placed so that DB is in a straight line with BE; therefore FB is also in a straight line with BG.

Let the parallelogram AC be completed; I say that AC is a square, that DG is a mean proportional between AB, BC, and further that DC is a mean proportional between AC, CB.

For, since DB is equal to BF, and BE to BG, therefore the whole DE is equal to the whole FG.

But DE is equal to each of the straight lines AH, KC, and FG is equal to each of the straight lines AK, HC; [I. 34]

Therefore the parallelogram AC is equilateral.

And it is also rectangular; therefore AC is a square.

And since, as FB is to BG, so is DB to BE, while, as FB is to BG, so is AB to DG, and, as DB is to BE, so is DG to BC, [VI. 1] therefore also, as AB is to DG, so is DG to BC. [V. 11]

Therefore DG is a mean proportional between AB, BC.

I say next that DC is also a mean proportional between AC, CB.

For since, as AD is to DK, so is KG to GC— for they are equal respectively— and,

Therefore DC is a mean proportional between AC, CB. Being what it was proposed to prove.